Zoning rules are not a constant

Harrisonburg's zoning ordinance and map has changed many times over the decades. A brief look at the history of land use at the site of The Link proposal in south downtown Harrisonburg.

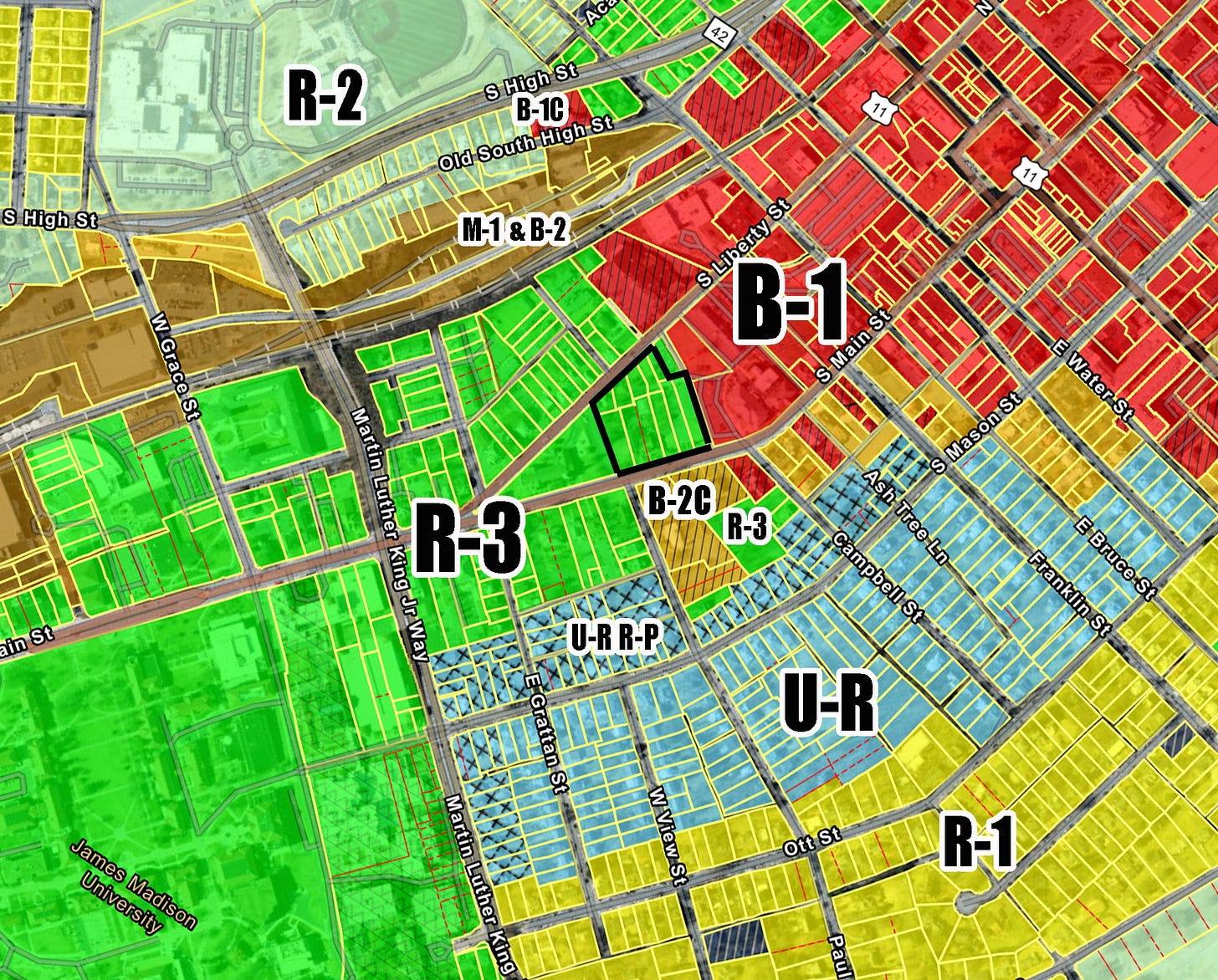

In the debate over whether Harrisonburg City Council should approve or deny a request to rezone several lots on the southern end of downtown from R-3 (medium density residential) to B-1 (central business district), I’ve read pleas to keep the property R-3. There are yard signs all over Old Town that say “NO to B-1C,” as if B-1 itself were a scourge rather than simply the zoning designation for most of downtown (the C indicates there are conditions). In the push to preserve the R-3 designation, the history and intent of R-3 itself is is worth a closer look. Thanks to city staff who answered my seemingly random questions about this.

To the extent that people know about land use policies, a common narrative about why we need zoning usually involves keeping housing away from noxious industrial uses. If you’ve ever walked or biked by the houses near the intersection of Liberty and Washington, you may have noticed those houses are not protected from industrial poultry plant smells. In my experience, Euclidean zoning is much more effective at keeping apartments away from single-family neighborhoods than it is at keeping factories away from housing in general. The 2021 housing study found that Harrisonburg “prohibits multi-family development for over 80% of the jurisdictional area” (page 98).

Harrisonburg didn’t have a zoning ordinance until 1939. Many of the oldest and most recognizable buildings downtown were built before we had zoning laws. That original 1939 zoning ordinance bears little resemblance to the labyrinthine document we have today. There have been a number of complete overhauls of the ordinance, and between those overhauls, many, many amendments to change what is allowed in various zoning categories. For example, quadplexes and boarding houses used to be allowed in R-2. Quadplexes are no longer a by-right use in R-2.

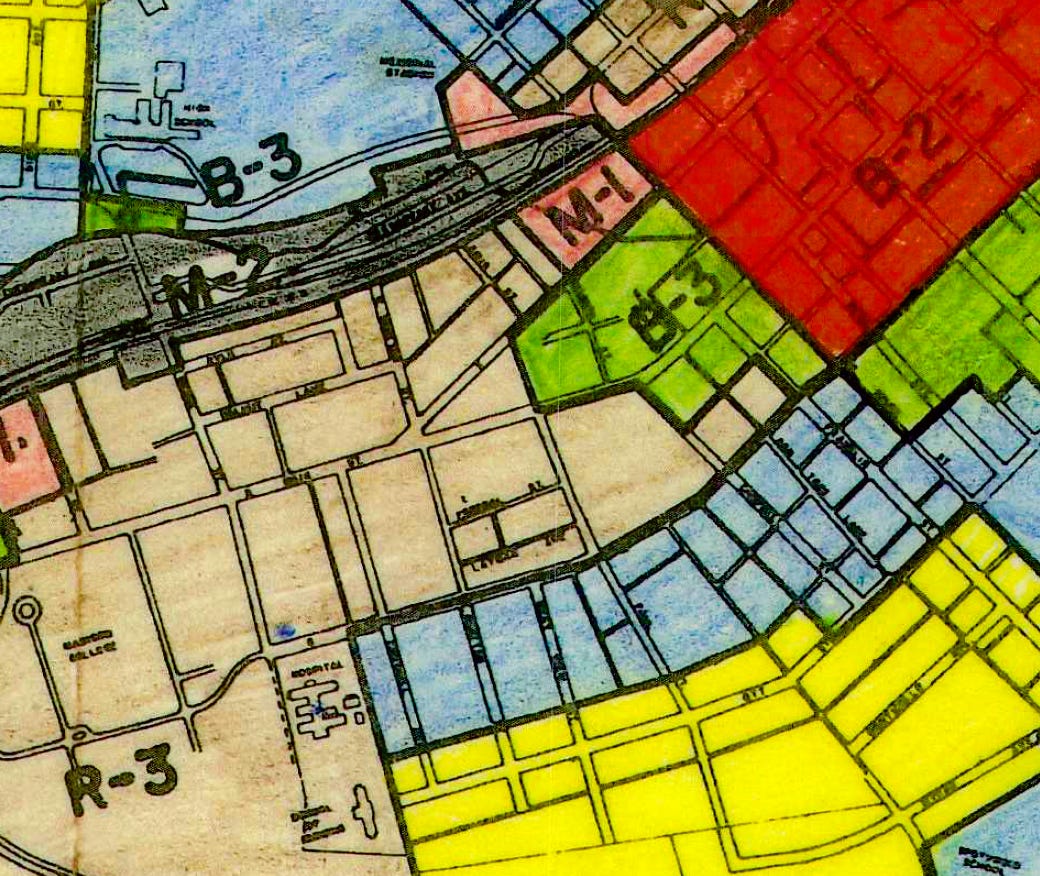

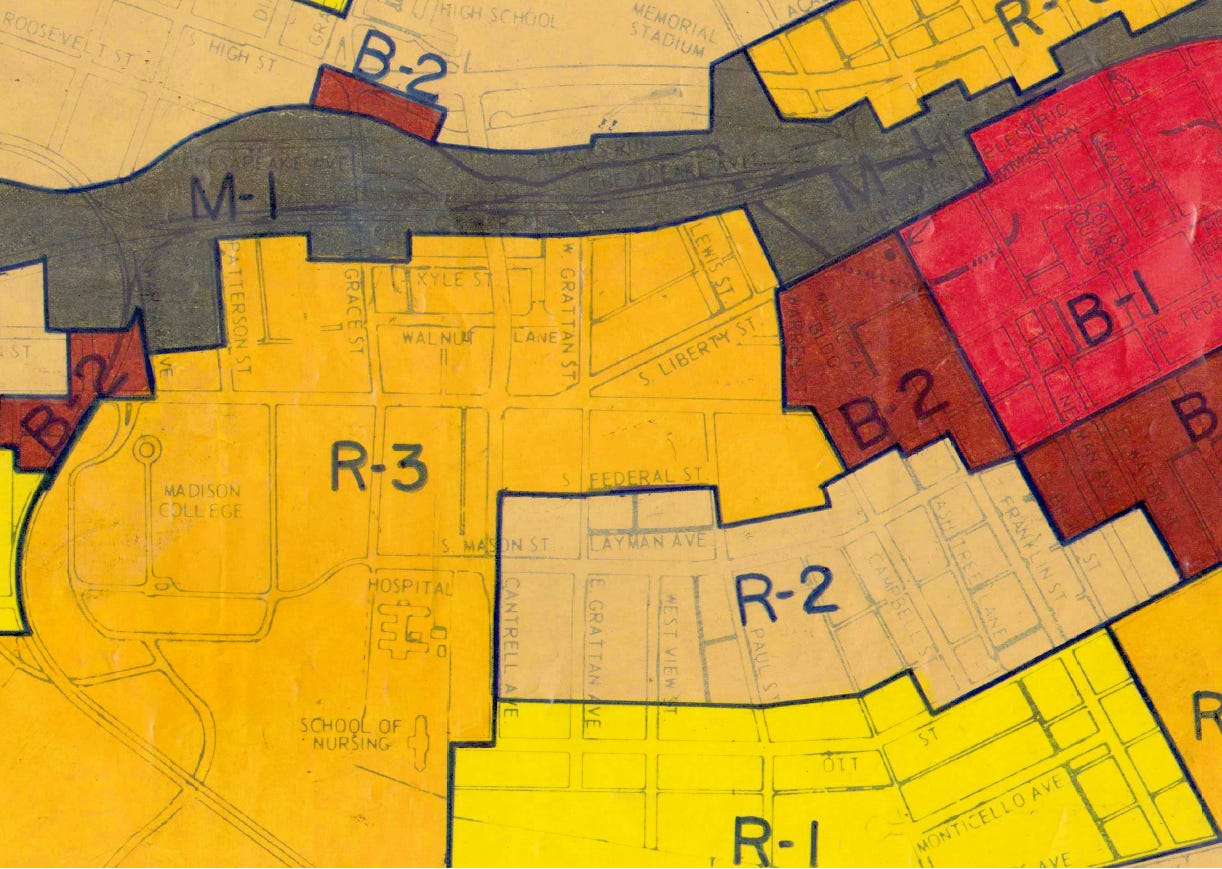

In 1939 and 1951, the properties where The Link is proposed to be built were zoned A-2 residential. That map, the designations, and the allowed uses changed over time. In the 1963 ordinance, one of the allowed uses in the R-3 multiple dwelling district was “multiple dwellings with no limitations as to number of dwelling units.” But at that time, these particular lots were zoned B-3 (general business district) which allowed for hotels, cold storage plants, bottling plants, car dealerships, and, of course, funeral parlors. Here’s a portion of the zoning map from 1963, showing those lots were zoned B-3 (green).

In the 1969 ordinance, R-3 was “intended for medium to high density residential areas [and] other permitted development including colleges, sororities, fraternities.” In 1977, the lots where The Link is proposed to be built show up on the map as R-3.

I wasn’t able to find much information about why that area was changed from B-3 to R-3 in that 1977 map update, but there are some odd references in the minutes of old city council meetings, like this:

“Having been a member of the Planning Commission when zoning R-3 was conceived, Mr. Denton pointed out that [rezoning properties to R-3] was done in order to relieve situations where sub-standard housing existed on a city street.” (Harrisonburg City Council minutes, April 12, 1977)

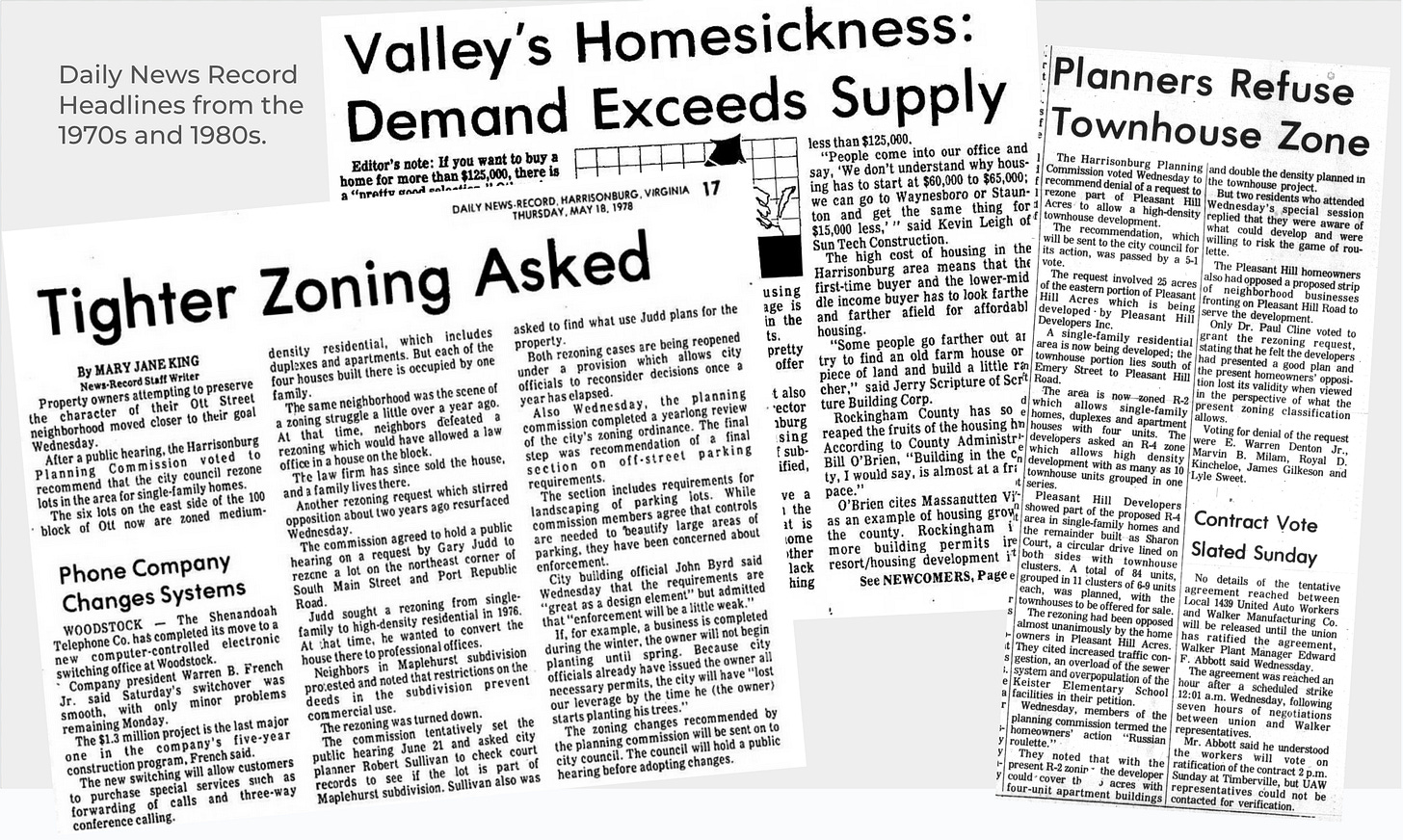

The 1970s and 1980s were a turning point for local housing policy across the U.S. Zoning ordinances became more strict as homeowners began to push back against new development and adaptive reuse of existing structures. A wave of downzonings swept the country, and Harrisonburg was no exception.

Harrisonburg’s zoning ordinance has been updated and amended many times over the years, which means the by-right permissions have changed with it. The trend over the past several decades has been toward more restrictions and rigidity. City staff explained to me that in the 1984 zoning ordinance, R-3 allowed up to 5 people in each unit, but in 1987, it dropped to 4 people per unit. In 2007 the city amended the R-3 district to require approval of a special use permit (SUP) to build multi-family units, even though that 2007 amendment did not go into effect until 2010. Like the Ship of Theseus, there’s virtually nothing left of the 1939 original.

My point is this: zoning maps and rules about what is allowed under various designations have changed significantly over time. When the land around the Lindsey Funeral Home was zoned R-3, the population of Harrisonburg was less than half of what it is today. City leaders and community members had different ideas about what could or should be built on these lots. A hotel or a bottling factory was never built on this site, even though they could have been built by-right until it was rezoned R-3. Similarly, townhomes have never been built here, even though townhomes have been a by-right use since the original Star Wars movie A New Hope was released.

There is no developer lined up to build luxury student townhomes or affordable housing on this site. Townhomes have not been built here, and will most likely continue to not be built here because this particular land is too valuable for townhomes. Respectfully, I must disagree with Professor Larsson’s conclusion: saying no to this rezoning is indeed saying no to development here.

We need more homes on less land in walkable neighborhoods, and with fewer cars per dwelling unit. Not only would The Link increase housing supply, it would increase supply in a location that is walkable and bikable to popular destinations, including downtown and JMU campus, as well as improvements like the upcoming Build Our Park and Liberty Street cycle track. This is preferable to adding dense housing to the outskirts of town, where residents are most likely to get in a car every time they leave the house.

An overwhelming majority of current Harrisonburg residents were born after 1977. R-3 hasn’t always been R-3 as we know it today. Our zoning ordinance and zoning map should continue to be updated to allow flexibility for Harrisonburg to adapt as the city grows and downtown evolves.

Why did Harrisonburg become a city?

Harrisonburg is one of just 41 independent cities in the US. Other than Baltimore, St. Louis, and Carson City, the other 38 are in Virginia. Cities in other states function similarly to the way towns function in Virginia: local governance overlayed on top of (or in addition to) the county government. Virginia towns are part of the counties they’re in, b…

Brent, thank you for this thoughtful piece—especially the very interesting zoning-map history.

A sincere question: hasn’t the City revisited—and in effect reaffirmed—the R-3 zoning on this plot on a periodic basis since 1977? When was the last time it was reviewed and reaffirmed?

I share in your aims of more downtown housing, walk/bike friendly neighborhoods, and truly affordable homes, as well as the public value of stewarding the culture and heritage that make historic districts like ours such special places to live. Good people can weigh these goods differently as we figure out how to harmonize them for the common good of all.

Most all of the people I know who oppose the current B-1C application still support developing the 473 S. Main St. property; our concerns are instead about the outsized scale and design of this specific proposal given its location in the heart of our historic district. In other words, many would welcome a smaller project at Lindsey—or a larger one in an area already zoned B-1C (or similar)—but placing B-1C here is the sticking point. As someone who supports the current proposal, do you think there might be common ground in exploring design changes that blend more gracefully with the surroundings and genuinely enhance our historic downtown, while still adding to our housing supply? Maybe that could be our way forward as a city!

I don’t think it is six-stories-or-nothing. On the feasibility of a smaller development, the price or value of the land depends on what someone is willing to pay, which in turn depends on what zoning allows. If it’s up-zoned to B-1C, the property owner can ask for a higher price because a six-story building will generate significantly more cashflows to the developer than a townhome complex (thus justifying a higher price for the land). If Council reaffirms R-3 (or a middle-scale zoning between R-3 and B-1C), however, the asking price for the land would have to come down, all else equal. More precisely, the price should come down to the level at which it would be economically feasible for a developer to buy the land, develop it, and still turn a profit. This is why I would argue R-3 (or other middle-scale) projects are indeed feasible on this property. (Many speakers during last night’s public comment period seemed to assume that the asking price of the land would remain the same regardless of the rezoning outcome. That assumption is not generally correct.)

While smaller developments may generate less cash flow for the property owner and developer, I’m sure we can agree that such private profits are not a measure of public benefit when considering rezoning applications. Affordable housing is a public benefit. So too is the history and cultural heritage that give a city its character. How do we best navigate the tradeoff between the two in this case?

I’ve learned a lot from your writing and would welcome a friendly chat in person sometime. It seems like we have some common interests with land-use, biking, and a love for our great city. Thank you again for your thought on this topic!

-Carl Larsson