What would Harrisonburg look like if we had a land value tax?

We get what we tax for: With property taxes, "blight is rewarded and building is punished." A land value tax could be a solution if General Assembly allows it.

You might not know who Henry George was, but many Valley residents in the late 19th and early 20th century would have been familiar with the idea of “the single tax,” otherwise known as a land value tax (LVT), which was popularized by George. His book Progress and Poverty was one of the best-selling books of the late 1800s.

The reactionaries at the Rockingham Register were not fans, referring to George as a “labor agitator” and his followers as “single tax cranks.” But his ideas outlived the Register. Here’s an excerpt from a column in the Daily News-Record in 1939:

“If taxes fell solely upon land instead of land and its improvements, clearly improvements would be facilitated. For instance, the single tax would facilitate housing … with housing now foremost among the nation’s needs, however, Henry George should be reexamined …”

84 years later we’re in the midst of another nationwide housing crisis. Some US cities, such as Detroit, are exploring taxing the value of the land (as opposed to the property that sits on that land). Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan put it bluntly, “the property tax system has two defining characteristics: blight is rewarded and building is punished.” Cars came about after Henry George’s time, but I don’t think he would have been fond of massive parking lots that create heat islands, make cities ugly and pedestrian-hostile, and are taxed at a fraction of the rate of adjacent buildings.

Exhibit A: the Floros parking lot in downtown Harrisonburg is currently assessed at $422,700 (for 0.59 acres) while the Jacktown building next to it is assessed at $1,436,100 (for 0.1 acres). Both properties are zoned B1, but the property that has preserved and improved its buildings contributes far more in tax revenue to the city than the former theater that was demolished and turned into a car storage lot. From a land use perspective, we can begin to see how taxing land instead of property would have a different outcome: It would be difficult to justify paying high taxes for an empty lot that’s not bringing in much revenue.

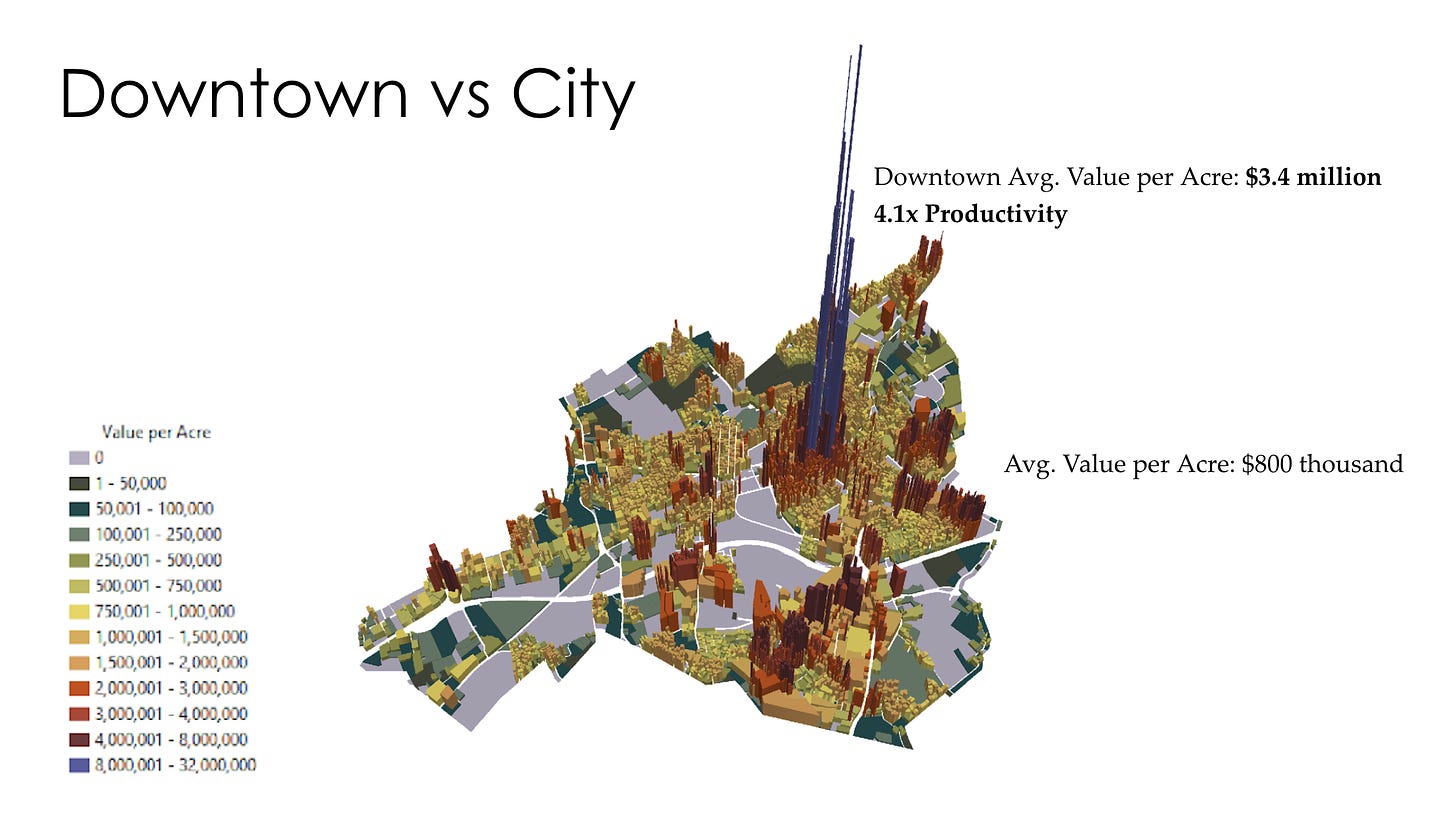

Geoaccounting analyst Joshua McCarty gave a presentation to the Harrisonburg Planning Commission in July that revealed just how much revenue the traditional mixed-use development in downtown creates. The 3D renderings of land value create a stark contrast with suburban-style development found elsewhere in the city. Where there is a dense mix of residential and business with less acreage devoted to parking, the value-per-acre is higher. Where single-family detached houses and strip malls with large parking lots predominate, the value-per-acre is lower.

As is the case in most American cities with an urban core that predates zoning and automobile-centric development, downtown Harrisonburg is the property tax engine of the city. I suspect this is also closer to the sort of compact, mixed-use development that would have been built elsewhere in town if we had tax policies that encourage maximizing the economic productivity of the land.

An LVT could be at odds with certain zoning regulations that restrict height, require large setbacks, or mandate a certain number of parking spaces per unit of housing or square footage of a business. If it were implemented the way it’s been done in Harrisburg (a city sometimes confused with Harrisonburg by out-of-state visitors) an LVT could incentivize the redevelopment of vacant properties, create more infill development, and increase housing supply.

In any case, this is all just a thought experiment because an LVT is not currently an option for Harrisonburg under Dillon’s Rule. As Wyatt Gordon reported earlier this year, “Under Virginia’s current code, only the Cities of Fairfax, Poquoson, Richmond and Roanoke are allowed to enact a land value tax.” But it’s not inconceivable that local LVT options could get bundled into state legislation aimed at increasing the housing supply in Virginia at some point in the future.