What impact do short-term rentals have on housing availability in Harrisonburg and Rockingham County?

They city and county have taken different approaches to regulating Airbnbs. The resulting impact on housing stock is reflected in new data from VCHR.

Airbnb may be a “disruptive technology,” but boarding houses and lodging houses in residential neighborhoods predate Harrisonburg’s first zoning ordinance in 1939. The second and third definitions on page two pertain to “dwellings other than a hotel where lodging for compensation is provided.”

To be fair, the boarding houses and lodging houses of the early 20th Century more closely resemble single-room occupancy (SRO) units than the epicurean app-ified “lodging for compensation” of today. Affordable housing of last resort for the working poor, SROs have been zoned out of existence in most U.S. cities. Meanwhile, short-term rentals (STRs) have proliferated over the past decade.

There are generally three schools of thought on modern day STRs: ban them all, let the “libertarian free market” decide, or find some middle-ground regulation to prevent the worst impacts of STRs. I fall into that third category. I’ve booked and stayed at Airbnbs elsewhere when no hotels are available in the area I’m visiting. We have a few STRs in our neighborhood that function more like a traditional bed and breakfast (the homeowner is present and some bedrooms are for rent). But when full living units that could otherwise be rented to local residents as year-round housing become full-time STRs, that makes our already dire housing situation even worse.

Rumors of Airbnb’s demise are greatly exaggerated. While NYC’s Airbnb ban has been grabbing headlines, you can still find an STR through Airbnb or Vrbo in most of the United States. Here’s one recent snapshot of the listings available in Harrisonburg and Rockingham County.

Harrisonburg struggled with how to regulate short-term rentals for years. It became clear that property owners could make more money temporarily renting out their basement apartment or second house on Airbnb than they could by renting year-round to local residents. If allowed to continue unregulated, working-class renters in Harrisonburg would continue to lose bids for housing to out-of-town visitors, and investors could buy up housing stock and turn them into full-time STRs.

After a lot of back-and-forth, Community Development staff and the Planning Commission landed on this regulatory compromise: the property must be the operator’s primary residence. This was intended to prevent outside investors from buying up housing stock and turning them into year-round mini-hotels. Under the by-right homestay option, homeowners can rent the house they live in to 4 or fewer guests for up to 90 nights per year, without having to go through the public hearing process. If the homeowner wants to do more than that, they have to apply for a special use permit and get approval from City Council.

Outside the city limits, those rules don’t apply. Rockingham County has no specific ordinance for short-term rental properties, and there has been a steady increase in STRs in the county over the past few years. Some towns in the county have regulations, but others, like Broadway, have rolled back their regulations.

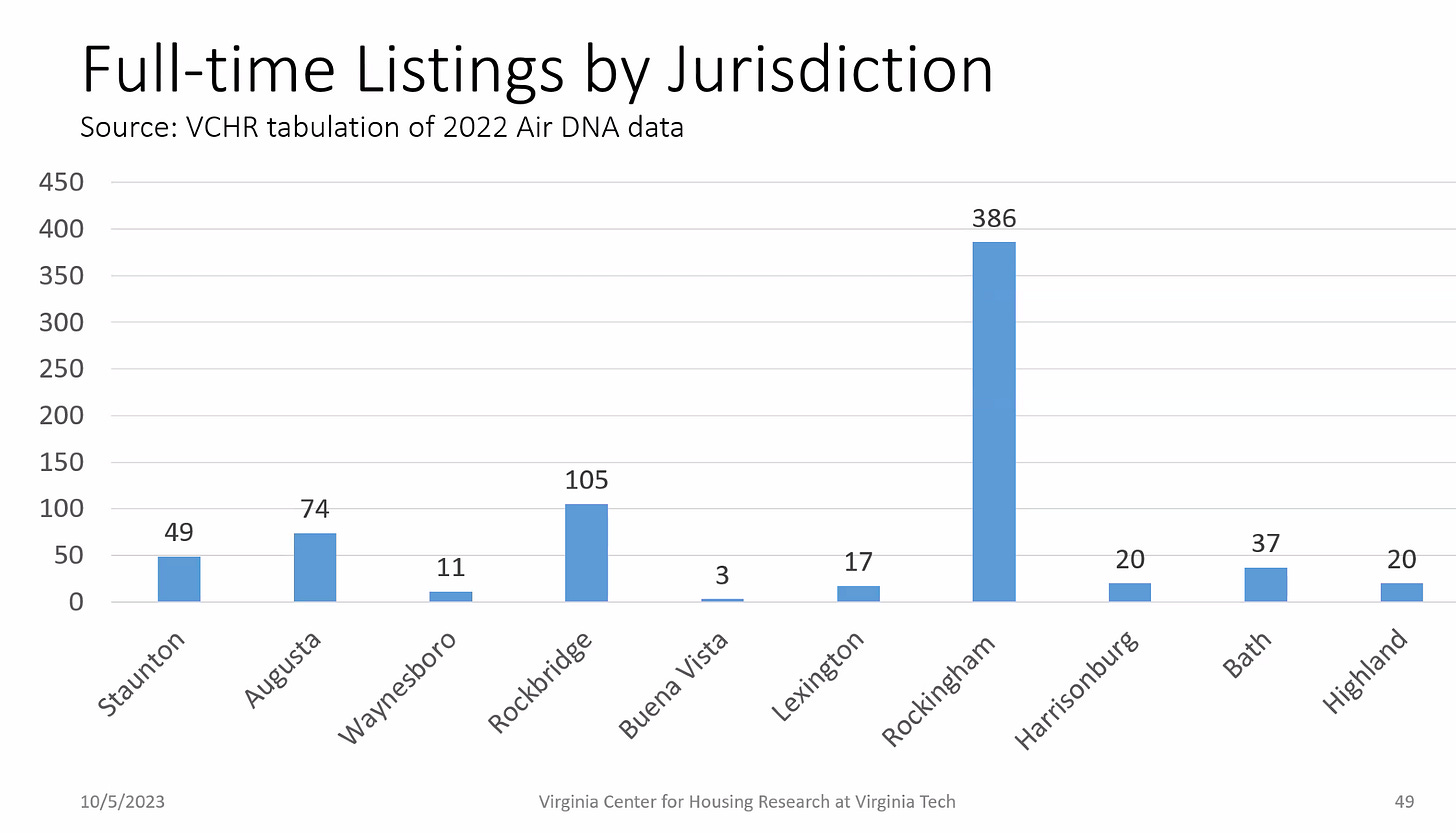

Last week the Central Shenandoah Planning District Commission (CSPDC) and the Virginia Center for Housing Research (VCHR) shared regional data from AirDNA (which includes Airbnb and Vrbo listings) about the impact of STRs on housing in the Valley. They make a distinction between full-time STRs (whole homes listed the entire year), occasional STRs (whole homes rented part of the time), and partial STRs (a room in a house where the owner is present). These charts focus on that first category.

The difference between regulatory approaches in the city and county is evident in these charts shared by VCHR. There are far more full-time STRs in Rockingham County than in Harrisonburg. The same holds for listings as a percentage of the housing stock.

It would be easy to look at these numbers and dismiss whole-home, full-time STRs as a non-factor in local housing availability. If our housing shortage was a forest fire, Airbnb would be a shot glass of gasoline. It’s not helping, but it’s not the root cause of our housing crisis. But let’s put the number of whole-home full-time STRs in the county into perspective: 386 is almost twice the number of homes currently available to buy in the city and county combined. That’s how low the available housing stock is in the Valley.

To address our local housing crisis we need more housing of all kinds in the city. Half a duplex rented as a full-time Airbnb is one less place for a local family to live. If (or when) Harrisonburg legalizes ADUs citywide, it’s important that those new units are actually housing for local residents. Under the city’s current STR regulations, new ADUs would be long-term housing by default.

Thank you Thank you Thank you

I have been so curious about this topic

“Wasted” housing is nothing new. I’m thinking of the McMansions and resort area houses that owners may only use a couple of weeks a year

BUT I have been concerned what all this short term rentals has meant for long term housing now that we have the AirBBNB etc. apps.

Good job and thorough research! I’m a big fan of facts.