Yes, Harrisonburg can meet our housing, revenue, and climate goals simultaneously

Land use reform is the most straightforward path to increasing housing supply and revenue while also achieving the city’s community emission reduction goals.

Two weeks ago I wrote a piece about legalizing affordable housing types, and this week I’ll attempt to connect the dots between housing, municipal revenue, and local climate policy. When I’m weighing whether to vote for or against a request in front of the Harrisonburg Planning Commission, two of the factors that I consider are impact on local housing supply and sustainability. The S word has come under increasing (and legitimate) criticism, but in this context I’m defining sustainability as lowering our carbon footprint per household as well as development that brings in adequate tax revenue to sustain municipal services in perpetuity.

A year ago, Harrisonburg City Council adopted climate goals aimed at the “reduction of greenhouse gas emissions at a speed and scale consistent with current science.” The most straightforward path to achieving the city’s community GHG goals is through land use reform. Land use policy impacts the amount of energy city residents use (or waste) at home, as well as the number of vehicle miles traveled (VMT) getting to and from daily destinations. The carbon footprint of denser, mixed-use developments is lower per household compared to low-density, use-separated detached single family homes (DSFH) located miles away from schools and businesses.

I used to live in an older apartment above Indian American Cafe in downtown Harrisonburg. In the winter I rarely had to turn on my baseboard heaters because the heat from the businesses below indirectly heated my apartment, as well as the apartments above me. Peter Calthorpe wrote a book about all the reasons denser multifamily housing has a lower carbon footprint per household than low-density suburban development. Here’s a key infographic from Urbanism in the Age of Climate Change that shows building emissions (in blue) and transportation emissions (in red) associated with suburban, “green” suburban, compact, and urban housing.

It doesn’t solve the problem to buy a hybrid and retrofit your house if all of that takes place 20 miles from your job. You’d still consume more energy (“suburban single family green”) than an urban household without the latest green tech (“urban single family”). And that has as much to do with associated transportation emissions as the size and efficiency of your home. (Bloomberg)

In addition to GHG emission reduction goals, there are also municipal budget factors to consider. Namely, does the property tax revenue from these proposed projects pay for ongoing municipal obligations such as schools, roads, transit, and other services the city will need to provide to them?

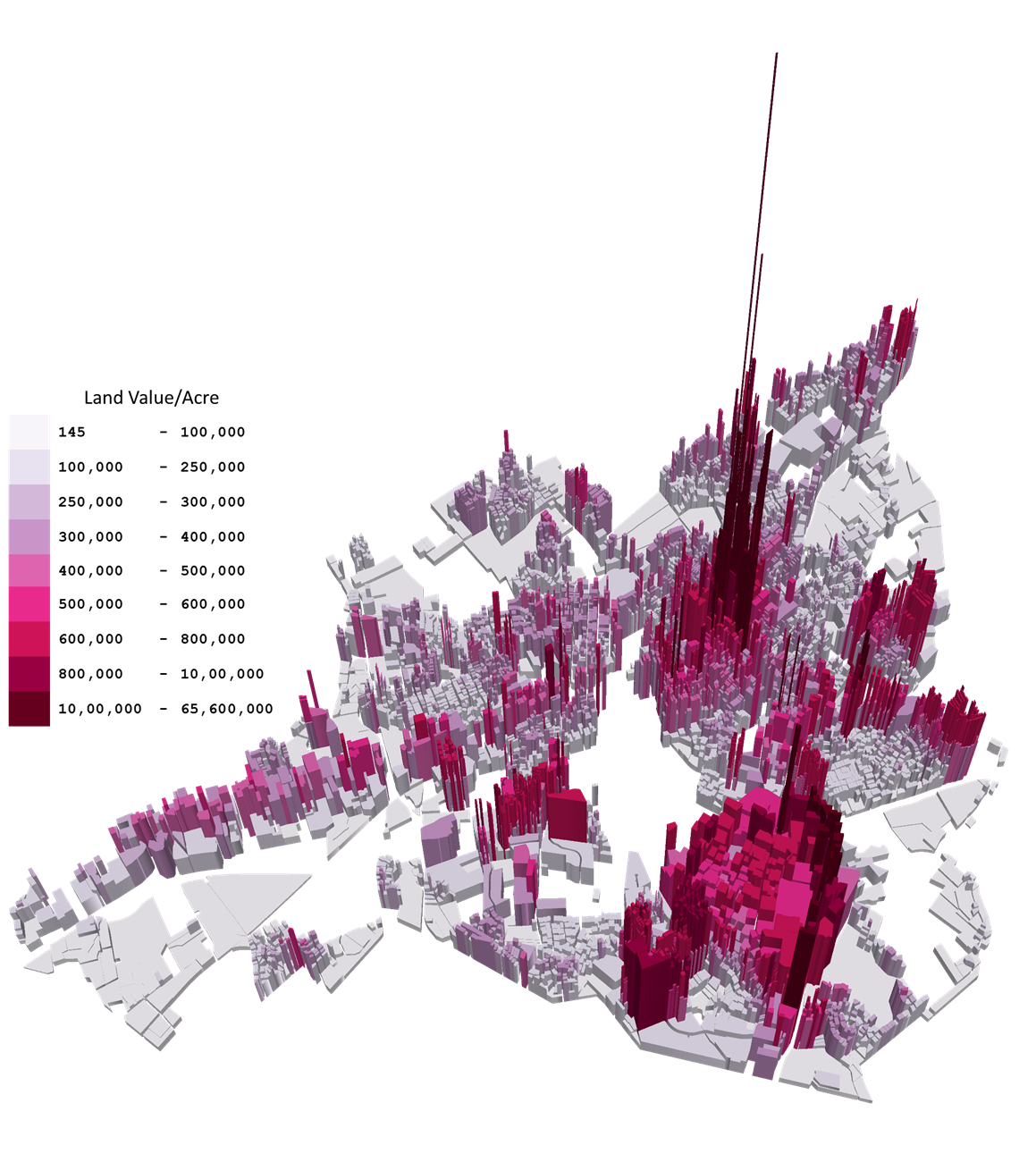

Last year geoaccounting analyst Joshua McCarty gave a presentation to the Harrisonburg Planning Commission that revealed how much property tax revenue traditional higher-density, mixed-use development in Harrisonburg creates. The 3D renderings of land value show a contrast between land value downtown, and car-centric, suburban-style development found in most other areas of the city.

You might expect the commercial area around the Valley Mall to be the economic heart of the city, but once you factor in all the large parking lots on that side of town, the revenue per acre goes down. Where there is a mix of dense residential buildings and businesses with less land devoted to cars, the value-per-acre is higher. Where single-family detached houses and strip malls with large parking lots predominate, the value-per-acre is lower. And where property is tax-exempt or the property taxes are exceptionally low, those parcels appear as blank white or light gray spaces.

We still need an analysis that shows a 3D image of the municipal expenses and liabilities for infrastructure and maintenance across the city. City decision makers need that data to make informed decisions about land use, but as of right now, I’m not aware of a full revenue-and-expenses analysis of Harrisonburg similar to the one done in Lafayette, Louisiana (watch the video below). Harrisonburg should put out an RFP for a detailed analysis of what land use patterns bring in revenue and which developments don’t pay for the infrastructure and services the city provides to them.

How can Harrisonburg foster more property tax revenue spikes like the one we see downtown? We should allow denser, mixed-use, by-right development in more areas in the city. Notably, there are no off-street parking requirements in the downtown central business district. We should repeal the off-street parking requirements that inhibit infill housing and small neighborhood businesses.

If you were thinking “surely the sales tax revenue from the big box stores is what really fills the city coffers,” this ACFR chart puts revenue sources in perspective. Sales and use taxes make up 11% and restaurant taxes make up 10% of revenue. Property taxes make up more than a third of city revenue (37%) and schools are our largest expense (30%). Land use reform can have a large impact on revenue.

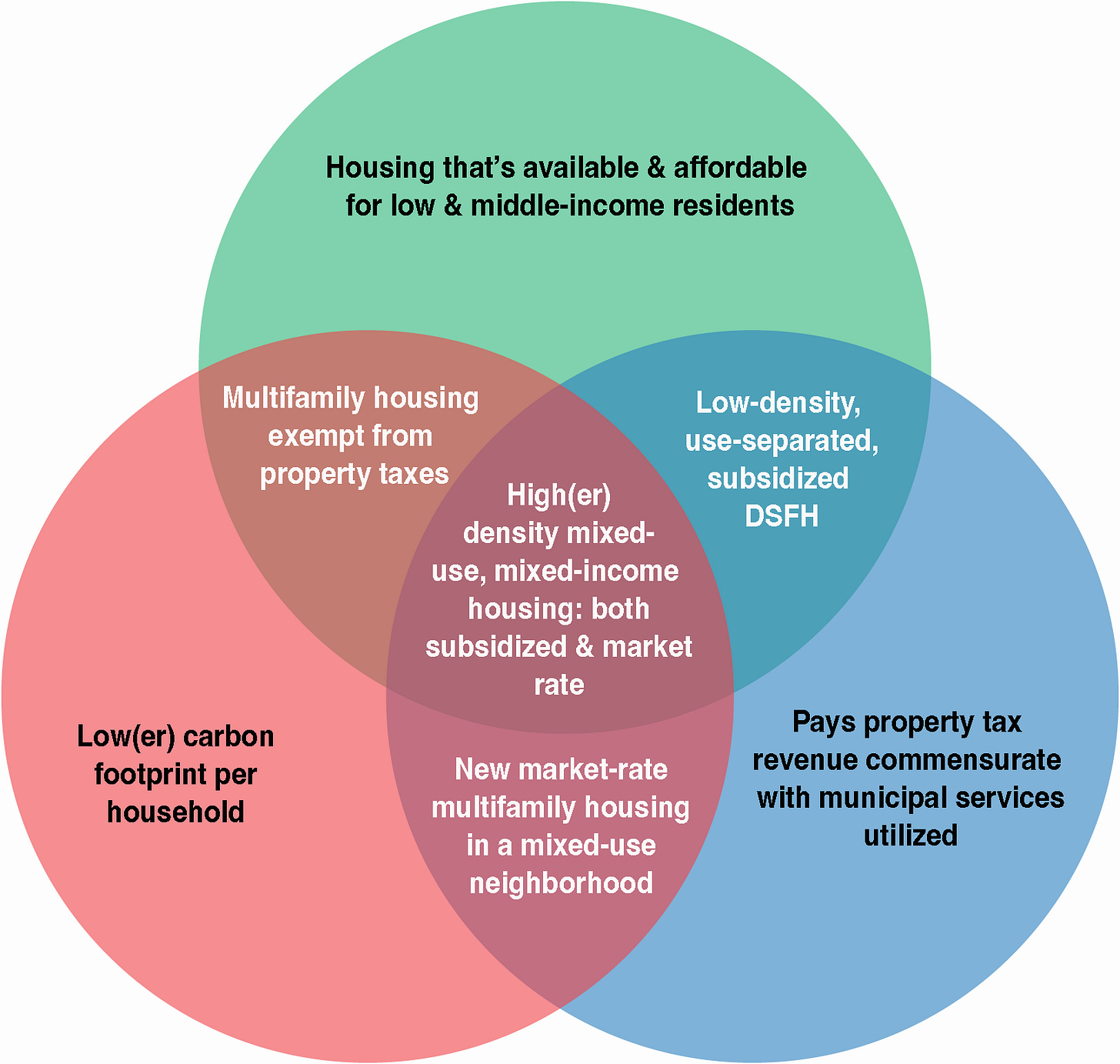

Affordable housing is important, and so is environmental and fiscal sustainability for the city. Properties owned by 501(c)(3) organizations don’t pay property taxes. That is not to say we shouldn’t support the development of affordable housing on tax-exempt land, but we should at least be aware of which properties are tax-exempt, and the implications of that exemption on city revenue and services. It’s possible to have affordable housing that is less environmentally sustainable (for example, subsidized single-family detached housing builds in rural areas that require long car trips). And we have some lower carbon footprint developments that are not affordable. We should revise our municipal policies and incentives to encourage development that is affordable, low-carbon, and fiscally sustainable. That requires shifting our approach to land use.

While it’s debatable whether low-density detached single-family housing (DSFH) can pay enough in taxes to cover municipal obligations for it, denser mixed-use, mixed-income development — some subsidized, some market rate — is key to balancing the city’s housing needs, revenue needs, and carbon emissions goals. It requires that we take an all-of-the-above approach. That means removing barriers to building a diversity of housing types — apartments, condos, multiplexes, townhouses, backyard casitas, manufactured housing, basement apartments — reducing lot size and setback requirements, and eliminating off-street parking minimums.

A better Harrisonburg is possible. We should reject the doomerism that says that improvement is a lost cause, or that there’s no point in trying to make it better. Understanding the connection between affordable housing and sustainable development should inform our decisions about how our city changes.