Why signs don't work: A local history of telling drivers to slow down

Harrisonburg's streets weren't always this distorted to prioritize the speed of automobiles at the expense of everyone else's safety. Our future doesn't have to be like this either.

If you’ve had the feeling that cars and drivers in your neighborhood have become more dangerous in the past few years, you’re not imagining things. Speeding is endemic, speed limits are rarely enforced, and the size of American vehicles is bloating. More than 40,000 people in the US die in car crashes every year (twice the number that die from homicide). And pedestrian deaths are at a four-decade high.

I’ve written about motonormativity before. It’s an insidious social norm that assumes that the convenience of drivers — not the safety of people — should be the dominant priority in our city. Motonormativity permeates practically every aspect of our daily lives. If that sounds overly dramatic, ask yourself: when you’re driving and you see someone riding a low-carbon form or transportation like a bike or a electric scooter in the street, is your first thought, “We should allocate some of the space currently devoted to cars to provide safe, protected lanes for them,” or is it, “They shouldn’t be riding in the street. Streets are for cars!” Why do we so rarely interact with our neighbors, except to occasionally honk at someone scrolling on their phone after the light has turned green? Does the fact that most parents can’t let their kids safely walk or bike to school bother you? Is driving in the US really even a choice? Or is there something obviously absurd about the way we’ve malformed our built environment to allow only one viable mode of transportation that is dangerous, expensive, requires a massive amount of space and energy, and is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the US?

We aren’t even aware that there are better ways of building communities and getting around until we visit a place where the safety of people not inside cars is given priority over the convenience of drivers. It’s difficult to overstate how abysmal and embarrassing the American traffic safety record is when compared with other rich countries. And even then, when we return home we tend to shrug off how brutal, inefficient, and harmful car-dependency is. Too bad American cities weren’t built like that, I guess. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Except American cities and towns like Harrisonburg were originally built for people, not cars. Automobiles were widely regarded as obnoxious interlopers, polluting the air, clogging up our streets, and crushing people to death. It’s worth uncovering this buried history to learn from it as we confront a new wave of dangerous driving and car-related injuries and deaths.

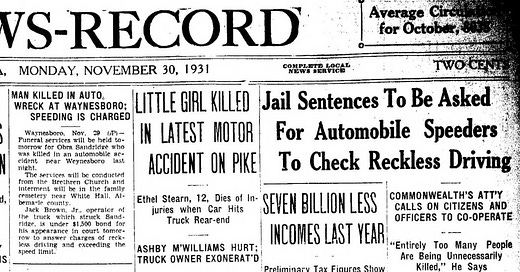

From the turn of the century through the 1940s, the headlines in the Daily News-Record were filled with tragic, gruesome accounts of children, pedestrians, drivers, and passengers killed and maimed by these newfangled personal transportation products. Here are a handful of examples from the archives of the Daily News Record that indicate just how foreign and unwelcome automobiles were:

In 1902 the Virginia General Assembly set the speed limit for “automobiles and other machines whose motive power is other than animals” at 15 miles per hour statewide and directed drivers to give priority to horse-powered vehicles.

Car ownership was uncommon. On May 19, 1911, the Roanoke Evening News reported on the “murder” of a car ordinance in Richmond that would have (among other things) prohibited “the running of automobiles by drunken chauffeurs.” The reporter noted that two of the members of the board of aldermen that voted against the ordinance owned automobiles (an obvious conflict of interest).

On June 24, 1915 the Harrisonburg Chief of Police issued a notice in the paper: “Owing to the large number of complaints by citizens because of the fast and reckless operation of motorcycles and automobiles, the police will at once take steps to apprehend all persons exceeding a speed of eight miles around corners or fifteen miles per hour on straight streets.”

An editorial in the Daily News-Record from 1916 accurately referred to drivers as “machine operators” and called for increased speed limit enforcement.

DNR, December 14, 1922: “Nearly all the cities of the Valley and surrounding section, including Harrisonburg, Staunton, Winchester, and Lexington are struggling at the same time with the problem of revising their automobile traffic regulations into much stricter form … One of the new regulations will undoubtedly restrict the parking of cars on main thoroughfares. A northern police official on a recent visit to the Valley, said he could not understand how an average of a funeral a day for auto victims was avoided in Virginia cities with the present parking system.”

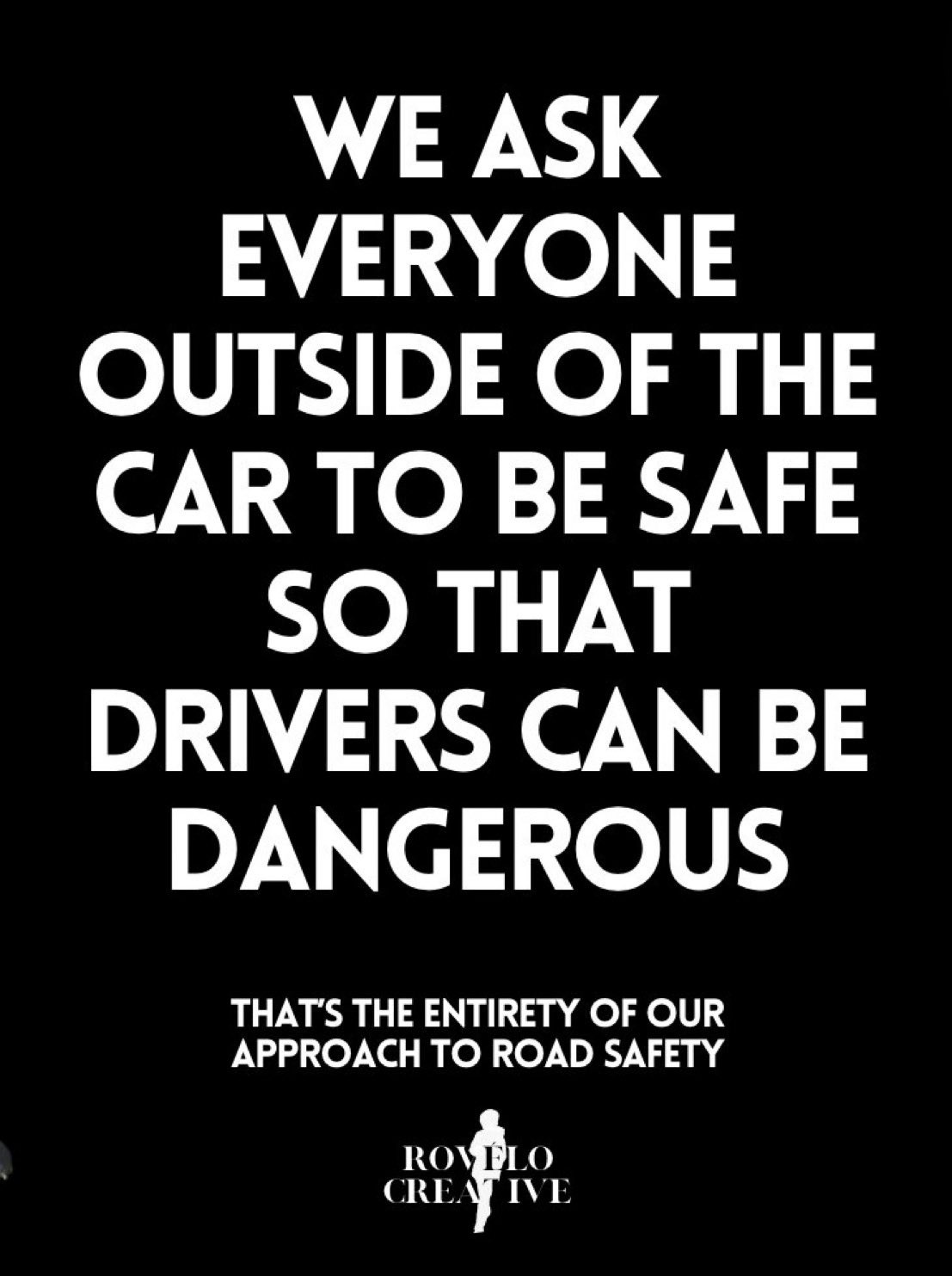

The commonly-accepted narrative of who was to blame for traffic violence began to change in the 1920s — the result of organized and well-funded efforts of Motordom. The auto industry successfully shifted the blame from their dangerous products — incompatible with the design of cities and towns — onto pedestrians and parents. Crashes became “accidents.” This played out in awareness campaigns like this one in in Harrisonburg and Rockingham County in 1936:

Some of these campaigns may have been well-intended, but decade after decade, they have proven ineffective in creating city streets that are safer for people outside of a car. The auto industry shamed parents (specifically mothers) for letting their children play in the street, which children had been doing in towns and cities for thousands of years. The automobile industry shamed people walking across the street for “jaywalking,” a “crime” invented by Motordom to shift the blame away from the deadly personal transportation machines that had commandeered our streets.

We’re still doing it today, presumably expecting different results. My neighborhood is currently going through the process of requesting traffic calming measures from the city to help slow the speed of cars cutting through residential streets. The first step in the Harrisonburg Neighborhood Traffic Calming Program is the placement of “team up to slow down” yard signs.

You can sense the exasperation that went into making this DIY sign I recently saw on the corner of Collicello and Rock Street. However, it’s unlikely this one is any more effective than the “team up to slow down” sign above.

The problem with signs and slogans is that they are easily and frequently ignored by drivers. This goes for speed limit signs as well. We’ve been begging drivers to slow down for more than a century. Simply put, signs don’t work.

Design and physical obstacles, on the other hand, cannot be ignored as easily as signs. Traffic calming improvements like speed humps, street trees, raised crosswalks, chicanes, and narrower roads force drivers to slow down, or risk damaging their car.

If you’re thinking, “what about speed cameras,” consider that the speed camera on E. Market St. has given more than 20,000 citations. That says more about the way we designed and engineered our roads than it does about the individual drivers. If the road is engineered to feel like a racetrack, we shouldn’t be surprised when motorists exceed the posted speed limit. Speed cameras are the wrong solution to the very real problem of cars traveling at unsafe speeds. If we want people to drive slower, we should build our roads accordingly.

While the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration is finally beginning to consider the safety of people outside of vehicles, state DOTs, local fire departments, and public works departments across the country need to accept their share of responsibility for the dangerous design of our streets, and change policies and designs to prioritize safety.

I’m starting to see some traffic calming adaptations added to certain roads in Harrisonburg in recent years (the road diet on Mount Clinton Pike, curb extensions on some newer sidewalks). Harrisonburg needs more of it, in more places. We should have universal street designs for low speed streets that make it physically difficult or impossible for drivers to move at unsafe speeds. Neighborhoods shouldn’t have to jump through hoops to ask the city to put safety over automobile throughput. Safety should be the default.

Our streets haven’t always been so contorted to prioritize and accommodate the storage and speed of automobiles. We don’t have to surrender and accept that car dominance is “just the way things are” in perpetuity. We pay the local taxes, not Ford, GM, Toyota, or Tesla. These are our streets. We should work to reclaim our neighborhoods from Motordom by prioritizing the safety of everyone outside of a car.

Harrisonburg needs a shared vision for a more vibrant human-and-nature-centered future. And we need the political will, advocacy, leadership, and stamina to implement that vision. That might look like pedestrianizing certain streets, eliminating parking requirements, and most importantly; updating our street design standards to force cars to slow down.

If you want to dive deeper into this intentionally buried history, read Fighting Traffic by Peter Norton.