How can we increase tree canopy cover in Harrisonburg?

Dillon's Rule doesn't help, but we can choose to prioritize trees and housing over parking lots.

Every time I hear a chainsaw in my neighborhood, I cringe. When a tree is in poor health and needs to come down, that’s understandable, but we’ve watched so many big, healthy trees around us get butchered for no reason other than “it was blocking my view.”

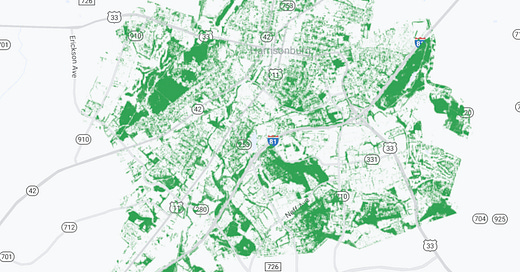

Tree canopy cover across the Chesapeake Bay watershed is declining. Harrisonburg has 26 percent urban tree canopy cover, which is slightly below the national average, and far lower than it needs to be to combat the repercussions of global warming. As weather patterns destabilize and we see hotter summers and greater chances of flooding, trees are our best bet for mitigating the worst effects of extreme heat and flash floods.

Parking lots and wide roads create heat islands, while properly placed street trees can result in a reduction of 20°to 45° in sidewalk temperature. Street trees can also help calm traffic and make streets safer for pedestrians.

A carrot without a stick

Harrisonburg Public Works is doing great things across the city, swapping mowed turf grass medians for native pollinator beds, and the Urban Forestry Program is diversifying trees on public land that will pay dividends in shade and wildlife habitat in the years and decades to come. The city can and should continue to plant as many trees on public land as we possibly can.

But there’s an elephant in the room: According to the city’s own 2021 Urban Forest Management Master Plan, only 11 percent of Harrisonburg’s tree canopy cover is on public property. Even if Public Works could maximize tree canopy cover on every last parcel of available public land (including all 191 acres of Heritage Oaks Golf Course) it still wouldn’t be enough. We need to address the other 89 percent: trees on private property.

Harrisonburg’s Conservation Assistance Program (HCAP) is an amazing initiative that reimburses private property owners for the cost of the trees they plant. It’s a wonderful “carrot,” or friendly incentive to encourage local residents to plant more trees on private property. And HEC, our municipal utility company, has a tree replacement program that private property owners can opt into. The Virginia Department of Forestry also recently announced $500,000 in grant funding for the Virginia Trees for Clean Water (VTCW) Grant Program to increase urban tree canopy cover.

But what about the “stick?” How can we prevent property owners from cutting down perfectly healthy trees on private property, where 89 percent of trees are located?

There are well-written tree protection ordinances, such as Seattle’s new tree protection code. So why don’t we just do the same thing in Harrisonburg? As is often the case in Virginia, Dillon’s Rule does more harm than good. Local governments in Washington state can do things under home rule that local governments in Virginia simply cannot do.

Virginia cities lack the authority to protect trees on private property

Local governments in Virginia have no authority to protect trees on private property unless that property is under development. From an Inside NOVA article last year:

The bill gives localities the option to require developers to replace or preserve existing trees in particular sites through minimum requirements. For example, a developer would have to make sure that 10% to 20% of a site is covered by tree canopy…

I see four key problems with Virginia’s tree replacement code (§ 15.2-961) in its current form:

Considering that the overwhelming majority of trees are not on properties in “the development process,” this is woefully inadequate legislation. This would do nothing to stop your neighbor from taking a chainsaw to a 100-year-old oak tree in his backyard simply because he doesn’t like raking leaves.

By singling out private property “during the development process,” the law effectively pits the need for affordable housing construction against the need for tree canopy cover. This is bound to foment friction between affordable housing advocates and tree canopy conservationists (I happen to be both). Cities can and should be full of both people and trees.

It doesn’t actually protect existing trees, it simply allows local governments to require replanting a certain percentage of the trees based on what was there when development began.

There’s nothing in the code that would prevent a property owner from clear-cutting all the trees on a parcel of land and then turning around to sell it to a developer who would then proceed to build as if there were never any trees on the site to begin with. By focusing so narrowly on the development process, it’s possible these ordinances could actually encourage clear-cutting trees on undeveloped land prior to land sales or rezoning applications.

Local governments in Virginia should have the authority to enact protections for trees on private property, regardless of whether that land is in the process of being developed. Under Dillon’s Rule, municipal governments currently lack that authority.

Trees, housing, parking: Pick two.

So what can we do about it? Long-term, we need to pressure General Assembly to give Virginia cities the authority to protect trees on private property that is not under development so local communities can enact ordinances like the ones in Seattle, Lake Forest, or Cambridge.

In the meantime, local residents can encourage City Council to eliminate the parking mandates in the current zoning ordinance. Look at this satellite image of apartments in Harrisonburg. What’s occupying more developed land: housing and infrastructure for people or housing and infrastructure for cars?

How many trees were removed to build actual housing, and how many were removed to make room for car storage? Harrisonburg currently requires a minimum number of off-street parking spaces per dwelling unit, so there’s already less buildable land for housing people.

To put it simply, we can pick two:

Housing for people

Tree canopy cover

Large impervious asphalt surfaces that create heat islands, exacerbate stormwater runoff, and are only used for car storage

If the city considers adopting a tree replacement ordinance under section 15.2-961 of the Code of Virginia, we must eliminate the parking mandates. These policies should be bundled together. To do it any other way would be to make housing for people our lowest priority, which would be absurd in the midst of a housing crisis. Developers will still build parking, but it will open up options for developers who want to unbundle rent from parking and charge separately for each. This allows residents who opt to live car-free or car-lite to pay less for rent.

In addition to lobbying the General Assembly to give local communities the ability to protect trees on private property, local residents who care about urban tree canopy cover can educate our friends and neighbors about the many benefits of native trees, the HCAP, the DOF VTCW grant, the harm that is caused by cutting down big healthy trees, and the problems caused by requiring and building so much parking. We can also push to amend or repeal Harrisonburg’s tall grass and weeds ordinance to encourage less short turf grass and more native wildflowers and grasses which capture carbon, lower the soil temperature, and support a healthy local ecosystem.

A recent analysis of urban density and green space in the journal People and Nature, states, “While there are tensions between density and urban green spaces, an urban world that is both green and dense is possible if society chooses to take advantage of the available green interventions and create it.” Despite Dillon’s Rule, it’s possible to build housing to meet our needs and have more trees in Harrisonburg.