Essential but insufficient: EVs as harm reduction

Electric cars are one part of the climate solution, but we need a transition plan — not just from gas to electric, but away from car dependency.

It’s human nature to want easy solutions to complex problems. We want gain without pain and progress free of inconveniences. In our pitifully slow transition from fossil fuels, switching from gas-powered cars to electric cars is a step in the right direction. But simply replacing the gas pump for the charger should not be our ultimate goal.

Governor Youngkin has said he would repeal Virginia's 2035 EV law if Republicans win both houses of General Assembly next month. This would be yet another short-sighted, climate-sabotaging move from Youngkin. Although the 2035 EV law already doesn’t go far enough, repeal would move us in exactly the wrong direction.

If our shared vision for the future looks like the sprawling suburbs and traffic-choked highways of today — only with electric instead of gas-powered cars — we’re in deep trouble. We need a bolder vision for a climate-resilient future. Most of us are too busy to fully comprehend just how severe and urgent the climate crisis has become. It’s difficult to wrap our heads around how many things need to change, so we tend to either shut down or shrug off necessary climate solutions as “unrealistic.” What’s truly unrealistic is expecting a livable future with more of the same unsustainable suburban development we’ve seen over the last seven decades. The good news is we can use this period of transition to make big-picture changes in our own community that will maximize the environmental impact of EVs.

There are environmental harms associated with mining the materials needed for EV batteries — chances are you’re reading these words on a lithium-powered device — but compared to the current harm caused by burning fossil fuel, it’s clear which energy source is worse for our planet. A recent Washington Post article put these harms into perspective, concluding that transitioning to electric cars is “much less harmful than if we stay with fossil fuels.”

Transportation is the largest contributor of greenhouse gas emissions in Harrisonburg (34.5%). Transitioning to EVs will lower that number, and we should divest ourselves of fossil fuels as quickly as possible. However, even if everyone purchased nothing but EVs starting right now, gas-powered cars would still be on the road for another 15 to 25 more years. We can’t wait that long, which is why we need to adapt our car-centric American cities and towns to be car-optional, rather than car-dependent. Transportation for America puts it like this:

“EVs are essential but insufficient to reach climate goals, and [strategies that allow people to get around without at car] reduce emissions while delivering other benefits like equitable access to opportunity, reduced urban footprint, and less need for battery minerals, which can relieve supply chain and global security pressures.”

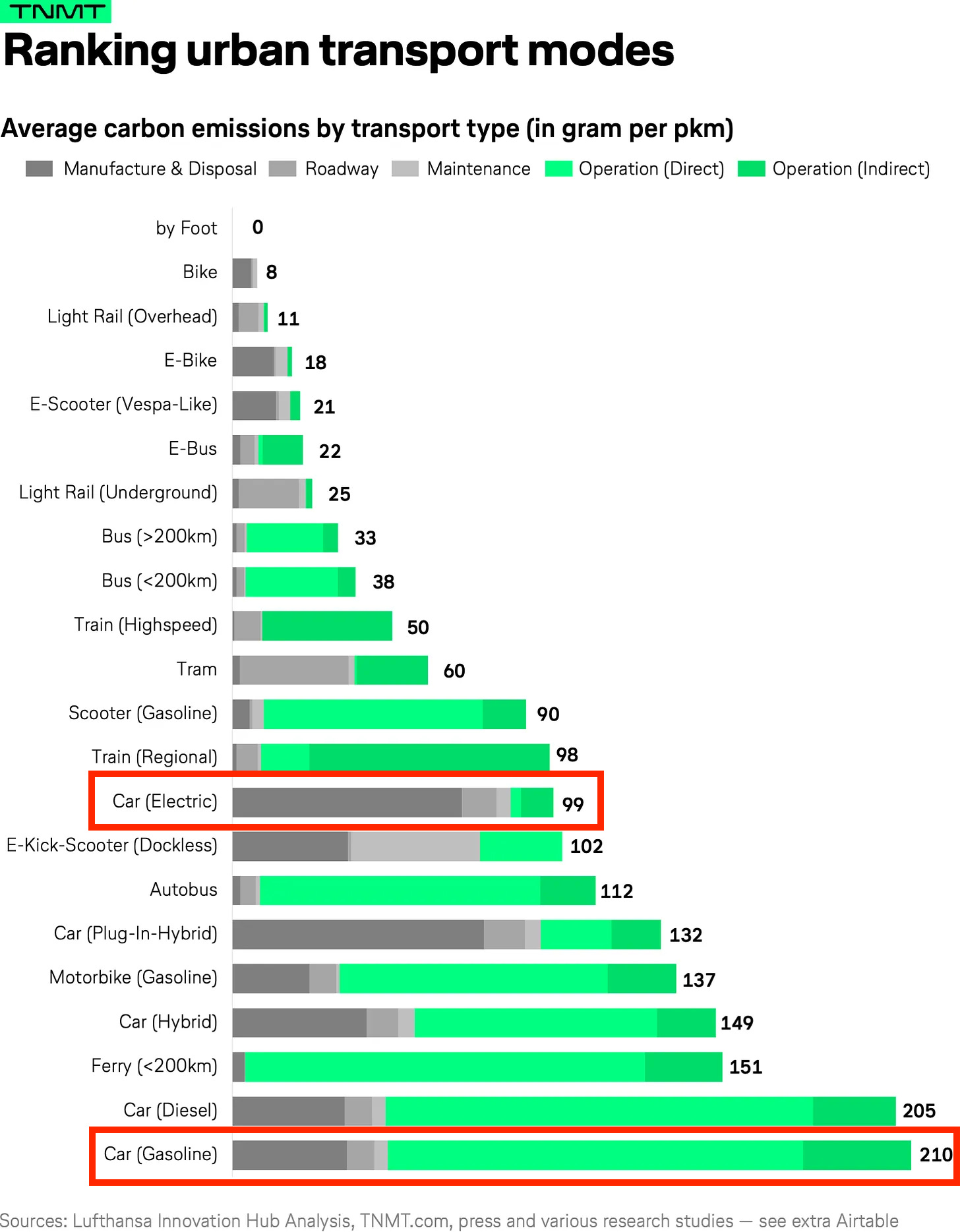

I’m focusing here on intracity transportation (getting from one point in Harrisonburg to another), not intercity (getting from Harrisonburg to Staunton). More than half of all trips by car in the U.S. are less than three miles (mostly intracity). Since we’ve designed our cities in such a way that virtually all trips must be made by car, it’s no wonder Americans have the highest carbon emissions per person in the world. But, EVs will take care of that, right? When we account for vehicle manufacture, maintenance, fuel, disposal, and car infrastructure, EVs have about half the carbon footprint of gas-powered cars. But that’s still far more than buses, bikes, and walking.

Harm reduction aims to decrease some of the worst consequences of addiction, not to stop or reverse it. If car dependency is the addiction, private EV ownership is harm reduction. We need to do better. We urgently need to phase out fossil fuel-powered cars and at the same time, we should roll back the municipal subsidies that prop up private car ownership.

In their Driving Down Emissions report, the authors at Smart Growth America write, “We’ll never achieve ambitious climate targets or create more livable and equitable communities if we don’t find ways to allow people to get around outside of a car.” The real solution to the environmental, social, and economic ills created by American car dependence is not an electric version of the suburbia we already have — it’s to make it pleasant, safe, and convenient to get from where we live to where we need to go without needing a car.

We need to look beyond the windshield

Technically I’m an EV owner (two wheels, not four). My spouse and I are currently able to live car-lite (two drivers, one car) and we’ve discussed the possibility of our next car being an EV. After all, what could be better for the planet than buying an EV? How about: not buying a car at all?

Most cars remain parked 95% of the time. Considering the average monthly cost of owning a car has surpassed $1,000, cars are a colossal waste of money, space, and resources. While widespread private car ownership is certainly in the best interest of the automobile industry, it’s not in our own best interests or the interests of future generations. But what’s the alternative? How do we get from the car-dependent city we have today to the walkable, car-optional city of tomorrow? Do I honestly expect everyone to walk, bike, or take the bus in a city that was built for cars?

It’s difficult to envision a car-optional future when we only ever see our world through the windshield of a car. But we owe it to future generations to try. We need a transition plan — not just from gas to electric, but a transition away from car dependency. Imagine if there were shared electric cars that were readily available in every neighborhood for anyone to use. If that sounds unworkable, consider that we already have shared EVs all over Harrisonburg that can be unlocked with an app. Now imagine that instead of just Bird scooters, the app could also unlock ebikes and Chevy Bolts. Not only is EV car sharing possible, it’s already being done in other U.S. cities. Car-sharing apps like Turo have the potential to allow more of us to let go of private car ownership. Climate solutions are all around us, hiding in plain sight.

Culdesac, a new car-free development in Tempe, Arizona, was designed around people, not cars. While we don’t have a local development like Culdesac (nor do we have light rail) a similar live/work arrangement can be found in downtown Harrisonburg. I’ve lived in four different apartments downtown over the years, and only one of them included car parking. I could walk or bike to most of the places I needed to be. The mix of residences and businesses close together (and the comparatively slow speed of cars through downtown) made that possible. More places in Harrisonburg should offer the same opportunity to live a car-optional life.

We don’t need to wait for the federal or state government to take action on this. Most of the decisions about how walkable or car-centric new developments are get made at city hall. Harrisonburg will soon be updating our zoning ordinance, which is a rare opportunity to change the future trajectory of development in the city. We can simultaneously welcome the transition from gas-powered cars to EVs while saying no to more car-dependent development, and yes to a more walkable, affordable, people-centered, climate-resilient future.